Waste management and Brexit: a chance to re-think strategy

Author: Kulvir Channa |

Since voting to leave the European Union, attention has been on the big issues of immigration and trade. However the forthcoming Great Repeal Bill, announced at Conservative Party Conference, will kick start the scrutiny of every line of European law; separating good from bad.

Although this dissection won’t attract as much attention as the more internationally-focused aspects of the UK’s disentanglement from the EU, trade, human rights, etc., it could have a significant impact on the public sector.

One policy area where the UK will soon have more control is recycling and waste regulation. Many local authorities see existing legislation – namely, the landfill tax – as an increasingly ineffective instrument and are keen to see reform.

Current European waste regulation

The European Union currently regulates for waste reduction and recycling improvements through the imposition of binding national targets set out in the Waste Framework Directive and Landfill Directive. These have committed the UK to, amongst other things, recycling 50% of household waste and reducing the amount of household waste sent to the landfill by 65% (compared to 1995 levels).

EU regulation has been relatively successful, pushing Government into action and improving how the UK manages its waste. By 2014 the UK recycled 44.9% of household waste and household waste sent to landfill had been reduced by 76% (compared to 1995 levels).

UK progress in achieving waste management targets set out in EU directives (Adapted from DEFRA’s ‘UK Statistics on Waste’, August 2016)

| EU target (to be achieved by 2020 unless stated) | UK progress | |

| Household waste | Reduce by at least 65% from 1995 levels

Recycle at least 50% annually |

Reduced by 76% by 2014

44.9% was recycled in 2014 |

| Packaging waste | Recycle or recover at least 60% annually by 2013 | 72.7% was recycled or recovered in 2013 |

| Non-hazardous construction and demolition waste | Recover at least 70% annually | 86.5% was recovered in 2012 |

The landfill tax: a high price for local authorities

The Government’s primary method of incentivising local authorities to achieve European targets has come through the form of a landfill tax. Introduced in 1996, the tax applies to every tonne of ‘active’ and ‘inactive’ waste sent to landfill, with a much higher premium for the former. Originally set at £7 per tonne of ‘active’ waste, the standard rate has increased every year since 1998 and is currently charged at the rate of £82.60 per tonne.

Although operators of landfill sites are liable for the tax, the cost is routinely passed onto local authorities and businesses. For some local authorities, such as Hampshire and Kent county councils, these costs can rise to above £13 million annually. In England, a relatively conservative estimate of the cost of the tax in 2014/15 was £223 million.

(Cost estimated by using the same proportions of waste paid at standard rate, lower rate and exempt in HMRC data on landfill tax collection and applying them to the total landfilled waste collected by English local authorities 2014/15. This is a very conservative estimate compared to the Local Government Association’s estimates that the tax cost local authorities £535 million in 2013/14.)

The five local authorities who paid the most in landfill tax, 2014/15

| Local authority

|

Estimated tonnes of waste paid at standard rate | Estimated tonnes of waste paid at lower rate | Estimated landfill tax payments |

| Hampshire | 166,723 | 145,255 | £13,381,493 |

| Kent | 162,528 | 141,600 | £13,039,105 |

| Birmingham | 156,592 | 136,429 | £12,711,550 |

| Essex | 155,587 | 135,553 | £12,501,349 |

| Lancashire | 145,140 | 126,451 | £11,644,560 |

An increasingly ineffective policy

Local government has begun to argue that the evidence on the landfill tax suggests recent changes in waste management have come about increasingly independently of any increases in landfill tax rates. In 2012, the Environmental Services Association calculated a three year extension to the landfill tax escalator then in force, peaking at £104 per tonne in 2017, would only reduce landfill usage by 3%.

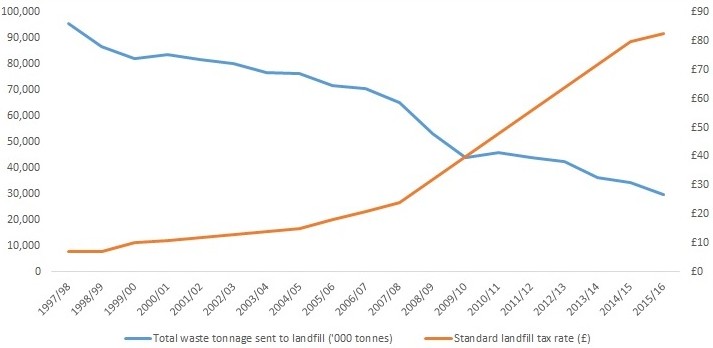

The Local Government Association has said “there is no evidence that further increasing the rate of landfill tax changes the already powerful incentive on councils to promote recycling”. As the graph below shows, although the spike in landfill tax rates in 2007/08 were initially successful – landfill waste declined, on average, by 11% annually up to 2009/10 – in recent years, despite tax rates almost doubling, landfill waste is declining at a much slower rate (5% annually).

Total waste tonnage sent to landfill vs standard landfill tax rate, 1997/98-2015/16

A chance to shift strategy?

Government has responded to these criticisms by only increasing landfill tax rates in line with inflation for the current and next financial year. Yet, further changes can now be considered with the vote to leave the European Union.

Reducing landfill waste would always be an aim of the Government, with or without Brexit, but the process of leaving the European Union gives it the chance to create a more effective policy than simply increasing landfill tax rates and hoping for improvements in waste management.

One alternative to the landfill tax is Government working with local authorities to devise a system of local recycling and landfill targets. Providing that these targets are reasonable, they still would provide local authorities with practical goals whilst reducing the financial burden the landfill tax places on them.